Kwame Kwei-Armah

Biography

Kwame Kwei-Armah was born in Hillingdon, London in 1967 to parents from Grenada. He grew up in Southall and observed fraught relationships between the white, African Caribbean, and Asian communities living there, witnessing the 1979 Southall riots first-hand. After tracing his Ghanaian origins, he changed his name from Ian Roberts at the age of 19. Kwei-Armah has had a diverse career as an actor on stage and television, as an artistic director, and as a playwright. His first play, Bitter Herb, premiered at the Bristol Old Vic in 1998. His nationally acclaimed Elmina’s Kitchen (2003) was the first play written by an African Caribbean to be produced on the West End. In 2011, Kwei-Armah became Artistic Director of Center Stage theatre in Baltimore, continuing to write and direct in the role, and in 2018 was appointed Artistic Director of the Young Vic. He is distinguished as the first African Caribbean director of a major British theatre but also by the breadth of his career preceding the appointment, including his significant and influential body of writing.

Kwei-Armah writes exquisitely, in a language that is peppery, poetic and full of wit; he articulates each theme without forcing his characters to be artificially articulate.

Writing

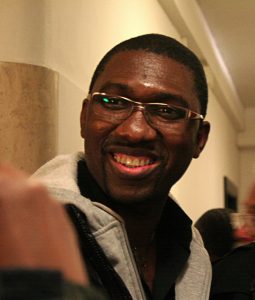

Kwame Kwei-Armah, 2008, Chermiah (CC BY-ND 2.0) via Flickr

Kwei-Armah’s plays are motivated by an unmistakable social imperative: he writes accurately and compassionately to describe the communities around him and ‘to be catalyst for a debate’ within them. His plays unfold in ‘forums’ of various kinds, peopled by characters who are both representative and questioning of the social, racial, and generational categories they represent.

In Elmina’s Kitchen (2003), three generations (plus an offstage fourth) of African Caribbean men grapple with conflicting ideas of their heritage and future. The Kitchen is the single location for the play’s turbulent and finally bloody proceedings, watched over by a portrait of the deceased matriarch Elmina. It went on to form the first part of a loose trilogy for the National Theatre about the African diaspora in contemporary Britain. Fix Up (2004) is again a play and a place, this time a ‘Black-conscious’ bookshop, the kind in which Kwei-Armah says he gained much of his own education. The elderly West Indian shop owner, young mixed-race girl, and reformed crack addict among its characters act as ciphers for the groups and issues they bring into the shop, but also question the functionality of such ciphers as the play becomes more morally and emotionally complex. By Statement of Regret (2007), the debating-chamber aspect of Kwei-Armah’s playing spaces is at the fore, with the action set in a Black political think tank where we hear ‘constant overlapping by others who have often got the argument before a sentence has been completed’ (stage directions). Kwei-Armah can be read as a fine classical dramatist who astutely presents debates on-stage in order to provoke them off-stage. However, that account might not capture the humour or disarming emotion in his plays, which never forget that their intellectual or cultural dramas are human dramas through and through.

Kwei-Armah has expanded beyond that founding trilogy into wider stories about immigration and continent-hopping musical epics, but his sense of the theatrical remains fixed to character and language. Kwei-Armah’s characters – first-, second-, and third-generation immigrants to Britain – are destabilised and even made vulnerable by their in-between cultural identities. Many of them, like Kwei-Armah himself, slip between accents and idiolects – ‘refined West Indian,’ ‘classic Black London’, ‘Nigerian but never in the office’. But the flexibility and force of these identities are also empowering: not simply weighed down by complex heritage, his characters are also bolstered, and, perhaps most significantly, they learn to move freely and creatively from their bearings. Nowhere is this effervescent potential as vivid as in the fast-moving, polyphonic language itself. ‘You’ve lost it, blood,’ Ashley says to his father in Elmina’s Kitchen, who replies in a ‘flash of temper’, ‘I’m not no blood wid you.’ The answer comes, ‘Regrettably, that’s exactly what you are.’

—Louis Rogers, 2018

Cite this: Rogers, Louis. “[scf-post-title].” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2018, [scf-post-permalink]. Accessed 30 January 2022.