Identifying with literature

Some people prefer to read books that are written by people who they see as being ‘like’ them; others read to find out about contexts and perspectives that are unfamiliar. At the same time, writers and their work are sometimes put in categories that relate to geography, race and culture, such as ‘American fiction’ or ‘Africana’. These categories affect how their books reach audiences and how their work is read.

But in reading or hearing the literature itself, readers often discover unexpected ways of identifying with the characters, contexts or experiences expressed in the writing.

Elleke Boehmer’s 2018 book Postcolonial Poetics: 21st-Century Critical Readings looks closely at how we read, and how our reading moulds our sense of ourselves in the world. Postcolonial writing, Boehmer argues, is particularly suited to involving us in imaginative acts of border-crossing and identification. In this TORCH Book at Lunchtime discussion, a group of commentators from different disciplines pick up on different aspects of the book, raising questions about the location and interaction of readers themselves. We hear from Richard Drayton, Malachi McIntosh, Ben Morgan and Robert Young, followed by a final comment from Elleke Boehmer. The speakers conclude that postcolonial writing whether from Africa, Australia, or Black and Asian Britain, is differently highlighted if we approach it from the point of view of the reader.

How do writers respond to being categorised?

Writers respond in different ways to how they might be seen by readers and other audiences. In this recording, the poet Vievee Francis talks about how she and her writing are viewed through the ‘filter’ of people’s preconceptions, which are often based on her appearance. She prefers not to be categorised in this way, and describes how she actively works to challenge and remove that filter with her writing:

Francis observes:

There are attempts to pigeonhole me. I actively fight it. […] That I am a black woman informs everything that I write, but that was not the determining factor for why I was writing the poetry. […] I simply do not write what people expect a woman who they see in the room like me to write.

In the clip, Francis also says that reading her poems out loud for audiences is an effective way of ‘exploding’ their filters so that they are no longer a barrier to their engagement with her poetry:

For a moment, I see them seeing me. […] And in that moment, they begin to listen, to really hear what I’m trying to do with my text.

We further explore the impact of performing or reading literature aloud on our ‘Performance and reading’ page.

How do we identify with what we read?

The Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds reading group project invited British readers of all ages to come together for book-group conversations about Black and Asian British writing. These readers, drawn from schools, the university, and the wider community in Oxford were mainly, but not only, white and British. One of the most interesting things that all the book groups discovered was that different or unfamiliar experiences were not a barrier to readers identifying with characters.

For many readers, finding points of familiarity along gender, age, geographical or other lines was important for their ability to enjoy stories from communities different from their own. For example, young women readers enjoyed reading about young women surviving and thriving in different times and places than their own.

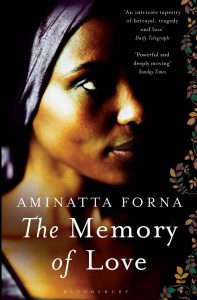

Often readers were also struck by finding experiences that were similar to their own in very different contexts. In some cases, universal human stories, like falling in love or starting a family, acted as a bridge, especially when reading about other cultures, such as Sierra Leone in Aminatta Forna’s The Memory of Love, or Somaliland and Eritrea in Nadifa Mohamed’s Black Mamba Boy. Or they enjoyed seeing characters from other cultures making their way in typical scenes from British society, like going out dancing or eating fish and chips.

The importance of alternative perspectives

While the majority of our Oxford readers were from white British backgrounds, those who weren’t enjoyed reading books that presented alternative perspectives to the ones often found in what is more typically considered ‘British’ literature. For such readers, seeing their stories represented in books can be profoundly validating. See, for example, what writer Alex Sheppard says of Zadie Smith’s writing:

She had a Jamaican mother and English father, like me. She grew up in a North London council flat, like me. She was a writer, like I aspired to be. To a bookish teenager, these facts were important.

I was an avid reader but it wasn’t until I read White Teeth that I saw myself, a brown working-class girl, reflected in literature.

Author Nikesh Shukla feels similarly:

The first time I read White Teeth, […] The thing that struck me at the time was it was the first time I’d seen a lot of the slang I’d said and heard in my North-West London suburb written down, in a book. It felt strange at first, then comforting. […] She’s one of the few writers who has been able to write about the London I grew up in, complex, multicultural London, lived-in London; not tourist London, Richard Curtis London where brown or black people barely exist, but my London.

In our study, some white British readers developed a new and more understanding perspective on immigrants in Britain today by reading about immigrant experiences in the past. ‘I saw that they were struggling,’ some said, ‘That they were cold and lonely.’ They found that the more they read, the more deeply they entered characters’ points of view, or the more fond they grew of the characters. Identifying in this way gave these readers new perspectives on their own contexts. They saw Britain from ‘the other side’. Sometimes these new perspectives were uncomfortable, because they made readers see the enduring divides and inequalities in British society more clearly.

All of this suggests that how we present literature to readers can be as significant as what is represented. When writing is framed as ‘other’ this can be an obstacle to our reaching out and identifying with characters or stories. Overall, we were happy to discover, people seem to find more to identify with in stories from other cultures or involving different and unfamiliar characters than we might originally have expected. The power of storytelling seems to override feelings of bafflement or alienation. Reading works as reaching out. We are drawn in by reading another individual’s amazing story.

We look more closely at how we are drawn in when we read on our ‘Reading and reception’ page.

Cite this: “[scf-post-title].” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2017, [scf-post-permalink]. Accessed 30 May 2022.

More on reading

| Approaches to reading | |

| Reading and reception | |

| Performance and reading |