Reading and reception

When we read, we are making sense not just of the words on the page but of the ideas being communicated to us. What happens in our minds or imagination in these moments? How do we connect with the ‘thought-world’ of the book, and could reading be a way of understanding and clarifying our own thinking?

Here are a few different responses that thinkers about literature have offered.

For me, reading doesn’t mean finding something lying behind the words, like a decoder, something that we have to dig down for, or unravel, untie or break open. Instead, I want to develop the sense of the meaning that is being transferred, or the truth, as lying on the surface of the page or being visibly there in the story. That act of transference of the story or poem or song from the speaker or the writer to the reader or the audience is fundamental. I as storyteller want to give you something and I believe it to be true and I want you to share in that truth.

Elleke Boehmer, Africa in Words

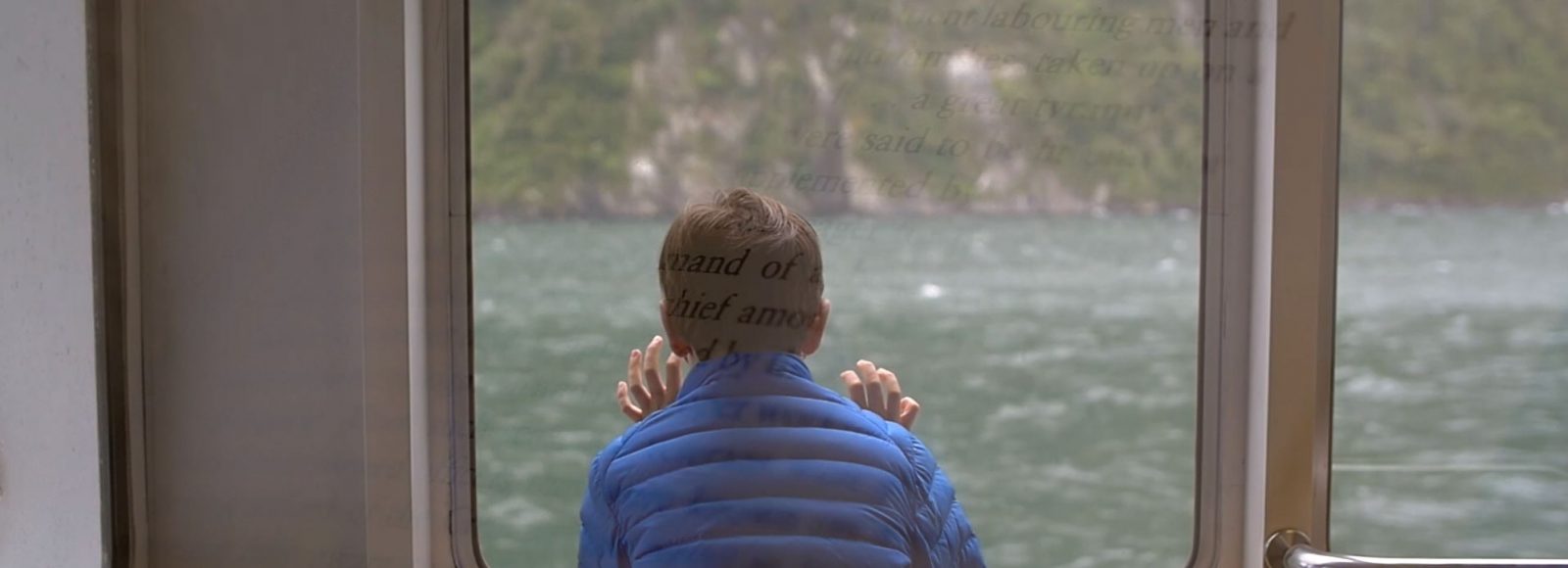

Embodied reading

In this video, Professor Carrol Clarkson explores how our reading asks us to commit ourselves, body and soul, to the emotional world of the text. To read, Clarkson suggests, is not just to see but also to touch and to feel.

Thinking together about human rights

The activity of reading gives us powerful ways of posing and exploring important questions about human rights, representation and justice today. Reading invites us to think together.

In this 2021 talk to the Oxford Postcolonial Writing and Theory seminar, Lyndsey Stonebridge offers readings from three texts to think about the different timelines—a time of exile, a moment of devastation, a time of waiting without end—that narrative and poetry invite us into.

Looking at Eric Auerbach’s Mimesis (1946, trans. Willard R. Trask, 1953), Mahmood Darwish’s Memory for Forgetfulness, August, Beirut, 1982 (1986, trans. Ibrahim Muhawi, 1995), and Behrouz Boochani’s No Friend But the Mountains (2018, trans. Omid Tofighian, 2019), she argues that writing can help us to relate better to other human life-times.

Lyndsey was speaking about her 2020 collection of essays Writing and Righting: Literature in the Age of Human Rights (Oxford UP) in which she makes the case for a renewed collaboration between the work of writing and the politics of human rights.

Cognitive theory

Professor Terence Cave believes that a form of cognitive theory helps us to understand how reading can ‘release the radical energies of literary works’. In his 2014 Balzan Lecture, he argued that:

Literature is a mode of thought that draws on the full range of cognitive processes, [and] exhibits their interconnectedness.

For cognitive theory, as we read, meaning at once spreads out in our minds and is constrained by the writing as we process the new elements that come to us. The words and lines at one and the same time flow through and shape our thoughts.

Reading as involvement

Professor Rita Felski has a different though related response. For her, reading is engagement or involvement, a recharging of our perceptions. Reading does not involve holding the text at arm’s length, suspiciously, and taking it apart to find its meaning. She believes that reading is ‘fundamentally a matter of mediation, translation, even transduction’. Critic Lorenzo Perez explains:

In her recent work, Felski has argued that literary scholars should spend less time looking behind a text for hidden causes and suspicious motives and more time placing themselves in front of it to reflect on what it suggests, unfolds or makes possible. What literary studies needs, she said, is less emphasis on ‘de’ words – demystifying, debunking, deconstructing – and more emphasis on ‘re’ words – literature’s potential to remake, reshape and recharge perception.

Felski asks us to think about why we love certain books and films. Why are some books important across cultures and different social spheres? See what she had to say about this question at our event in Oxford in November 2017:

Cultures and ideoscapes

Professor Simon Gikandi has also reflected on this. He argues that our reading is moulded by the cultures and ‘ideoscapes’ in which we find ourselves. In one of his key books, Reading the African Novel, he focuses on how the symbols and structures of the novel shape our reading. He believes that this is something that applies across all fiction, and therefore that African novels can be as accessible to us as, say, American or Caribbean novels, as long as they are written in a language we can understand.

In her podcast Staying Alive: Poetry and Crisis, Professor Adriana Jacobs invites eight contemporary poets to discuss how poets respond to crisis and the forms and language that they use to address it. Each episode features the close reading of a poem as a way of drawing listeners into the conversation, so they too can participate in the work of observation and critique that shapes this poetry.

Find out more about how readers in the Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds reading group project approached literature and writers from cultures and contexts that were different from their own on the ‘Identifying with literature’ page.

Questions

More on reading

| Approaches to reading | |

| Identifying with literature | |

| Performance and reading |