Close reading of Diana Evans’s 26a

Tessa Roynon

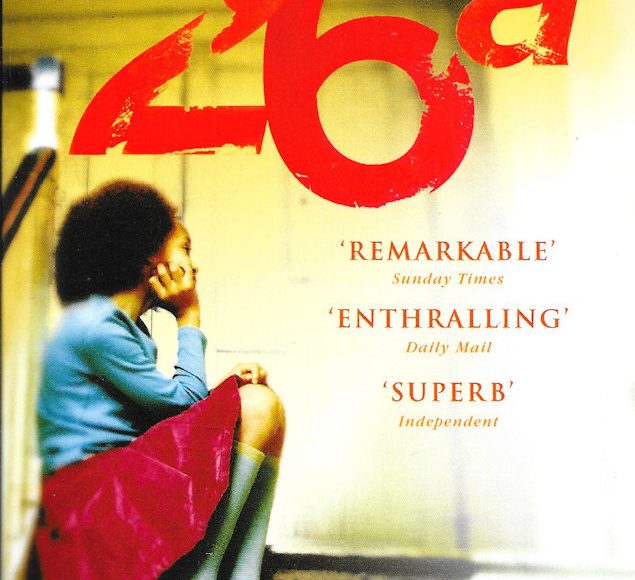

The analysis is of the following paragraph from Diana Evans’s 26a (Vintage, 2006), p. 45.

The night before they left, Georgia and Bessi – and Kemy was allowed too because it was a big goodbye – stood at the window in the loft and looked at the evergreen tree. The moon was lying in a silver hammock, behind the tree. They had the same feeling at the bottom of their stomachs, the tremor of an oncoming journey, the feeling that this night was the end of here and tomorrow would be an unknown, a dream that was not a dream, another sun and moon, different trees, different beds. Somewhere in the darkness the world would transform. Their house would go spinning in whirls of tornado and then slow down, and they would drift. They were full of hope, and sorrow. And fizz.

The three of them held hands, and Georgia prayed.

‘My first book is about the loss of a twin, what happens beyond that loss’, says Diana Evans in a 2018 BBC radio interview. Critics and reviewers to date have understandably focused on the ubiquitous ideas about ‘twoness in oneness’ in this text (26a 42): on Evans’ engagement with traditional Igbo beliefs about twins (see Boehmer’s article); on the symbolic relationship between Georgia and Bessi and biracialism; dual national identity and two home places; on split versus unified consciousness, and so on. While conceptions of doubleness are clearly central in the novel, it’s arguable that Evans is equally concerned with ‘what happens beyond’ doubleness, twinhood and duality. In the passage chosen here, in which not two but three sisters stand together on the eve of their departure for Nigeria, they imagine a transforming world. This moment epitomizes the high value the novel places on multiplicity or more-than-twoness, which Evans configures as a potential salvation in the face of binaries that cannot be sustained.

While the three girls’ speculative vision of their house ‘spinning in whirls of tornado’ brings to mind Dorothy’s displacement and fraught journey in The Wizard of Oz (45), after acclimatizing to their new life in Sekon (in suburban Lagos), they realize that ‘home had a way of shifting, … Home was homeless’ (54). Rather than the ‘drifting’ that they dread before the relocation, Georgia and Bessi learn that home ‘could exist anywhere, because its only substance was familiarity’ (46). Evans here constructs a paradigm of affiliation that allows not merely for the duality of Britain and Nigeria, but for multiple or infinite locations. Both Bessi and Kemy separately experience this ideal condition of diasporic life, termed by one critic ‘cosmopolitan belonging’ (Holland 555), through their respective visits to St Lucia and Trinidad. The Caribbean constitutes a third space in their lives, one point on the triangle across the Atlantic that Bessi traces on her floor map (132). Together with the ghostly Gladstone’s emphasis on the instantaneousness of the past, present and future – another significant trio (25) – these details exemplify Stuart Hall’s contention that identity and experience are neither singular or binary, but rather ‘multiply constructed’ (Hall 23).

Throughout 26a, Evans supplements doubleness, or transforms it into multiplicity, with striking frequency. For example, within the Hunter family, the often-invoked formulation of ‘the Little Ones’ is made up of ‘Kemy and the twins’ (9, 52, passim), while the epistolary chapter relating Bessi’s time in St Lucia involves an exchange of letters and messages between all four sisters (including Bel, the eldest), not just the twins. It is ‘Georgia, Bessy and Kemy’ that watch the film of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (94); Kemy, Georgia and Bessi who are caught by their father smoking weed together; and more than once the trio are compared to ‘triplets’ (17, 170). After Georgia’s death, Bessi and Kemy realise they are ‘two thirds of three’ (219), and Kemy, as ‘one third of three’ is key to the still-living twin’s survival. The author is careful not simply to substitute the ‘triplet’ paradigm for the ‘twin’ one, however: in a different formation, it is Bel and Bessi who together prepare Georgia’s body for her burial, and the eldest sister is a constant, nurturing presence throughout the text. Through the sheer number and variety of social configurations that Evans depicts – in shifting sibling groups, in flexible friendship groups, and in romantic entanglements – she privileges both the idea of acting collaboratively, and, implicitly, the idea that multiple identities are within each individual.

The numerous selves that make up Ida, the girls’ Nigerian mother, are expressed through the traditional West African sense of the connection between herself and her ancestors: it is not just she who wields the knife at the drunken Aubrey, for example, but a trio consisting of her own mother and grandmother besides herself. Equally significant is her quilted ‘magic dressing gown’, made not from two fabrics but from three, including one from Harlesden, one from Lagos and another designed by her mother (39-40). This emphasis on things in threes, or on what we might call the ‘powerful beyond-binary’, recurs throughout the text. On the eve of the family’s journey to Nigeria, for example, in the passage above, the Little Ones stand in their ‘triangular’ attic (58). ‘The three of them held hands’ while they envision their future and pray for their past (45). Evans’s syntax in the excerpt’s first sentence movingly mirrors this physical configuration – the parenthetical Kemy stands between the two halves of its main clause, as she does between her twin sisters. The trio’s envisioning of ‘another sun and moon’ anticipates the agonizing ‘one third of the moon’, at the novel’s end (229), under which Bessi finally has to relinquish Georgia’s spirit.

The flock of ‘night birds’ at that ending, meanwhile, which are Bessi’s only consolation, embody Kemy’s staunch belief in ‘strength in numbers’ (131), and they articulate the sense of survival and transcendence through multiplicity to which the novel as a whole subscribes. It is in this respect that Evans’s text fulfils Dr Jekyll’s prediction at the end of Jekyll and Hyde (1886) in which he anticipates that ‘others’ will ‘outstrip’ his belief in human doubleness. ‘I hazard the guess’, he says, ‘that man will be ultimately known for a mere polity of multifarious, incongruous, and independent citizens’ (Stevenson 77). Each one of us, in other words – and as Evans enables us to see – is like a cosmopolitan city, peopled by varied and numerous selves.

~

Works cited and further reading

Boehmer, Elleke. ‘Achebe and his Influence in some Contemporary African Writing’. Interventions 11.2, 2009: 141–53.

Evans, Diana. 26a. London: Vintage, 2006.

—. ‘Meet the Author’. BBC News programme, 10 May 2018.

Hall, Stuart. Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands. London: Penguin, 2017.

Holland, Samantha Reive. ‘“Home had a way of shifting”: Cosmopolitan belonging in Diana Evans’s 26a’. Journal of Postcolonial Writing. 53.5 (2017): 555–66.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. London: Scholastic 2016.

Cite this: Roynon, Tessa. “Close reading of Diana Evans’s 26a.” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2018, [scf-post-permalink]. Accessed 29 January 2022.