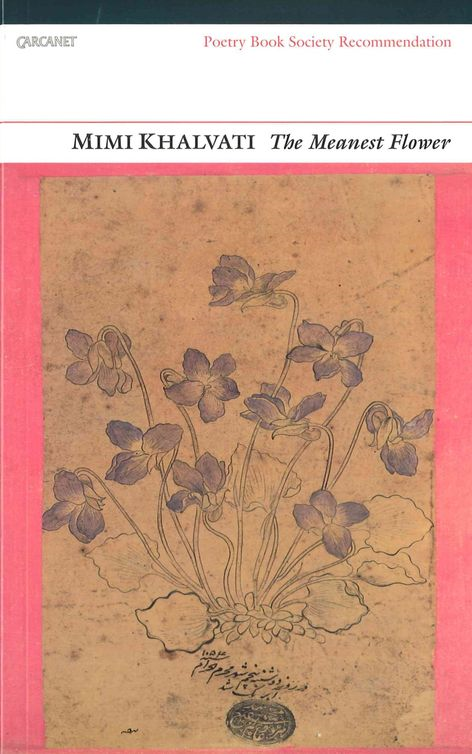

‘The Presence of the Ghazal in The Meanest Flower (2007)’

Holly Fathi

Ghazal: It’s Heartache

When you wake to jitters every day, it’s heartache.

Ignore it, explore it, either way, it’s heartache.Youth’s a map you can never refold,

from Yokohama to Hudson Bay, it’s heartache.Follow the piper, lost on the road,

whistle the tune that led him astray: it’s heartache.Stop at the roadside, name each flower,

the loveliness that will always stay: it’s heartache.Why do nightingales sing in the dark?

Ask the radif, it will only say ‘it’s heartache’.Let khalvati, ‘a quiet retreat’,

close my ghazal and heal as it may its heartache.

Ghazal: a lyric poem in couplets with a repeated rhyme. Typically a description of the beloved’s beauty, a lament of the poet’s separation from the beloved, or a description of a natural scene.

Reviewers often position Mimi Khalvati as a ‘Persian poet’ due to her inclusion of Persian imagery, form, and the occasional line of Farsi in her poetry. Often, she makes use of the ghazal form, which is known as ‘the most important Persian lyric’. Through her collections, the ghazal appears in various guises, such as in her poem ‘Ghazal’ or in The Weather Wheel (2014), which consists of poems structured in ghazal-like couplets.

Due to the appearance of these Persian literary signifiers in her work, Mimi Khalvati has not been able to shake the label ‘Persian poet’. This is a designation that perturbs Khalvati, as she noted to Vicki Bertram in interview: ‘I would like to be seen as a British poet, and I don’t think I’ve really been accepted as one.’[1]

But the tendency of reviewers to attribute Khalvati’s use of the ghazal simply to her ‘Persianness’ discounts her poetic skill, her deliberate use of the ghazal form for its particular aesthetic and affective qualities. The formal possibilities of the ghazal are such that Mimi Khalvati is able to use it to communicate certain emotions that are not possible in other poetic forms. We can see this in her collection The Meanest Flower (2007), and specifically in the first section of this collection. There, Khalvati uses both the sonnet and the ghazal together to reflect on her memory and her childhood. The title, ‘The Meanest Flower’, comes from the closing couplet of William Wordsworth’s ‘Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood’ (1807):

To me the meanest flower that blows can give

Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.[2]

If the intention of ‘The Meanest Flower’ is to summon thoughts about her childhood – indeed, ‘thoughts that do too often lie too deep for tears’ – the ghazal is a form that can help communicate such feelings. After interviewing Khalvati, Marius Kociejowski wrote that the ghazal form gives Khalvati ‘permission to be rhapsodic or sweet in a way she wouldn’t dare attempt otherwise and as such it enlarges her range of linguistic expression’.[3] Just before the ghazals in the section, Khalvati writes:

What were the thoughts that lay too deep for tears?

Oh, monkey-child, it’s time to lay them open.[4]

Three ghazals that follow – ‘Ghazal: It’s Heartache’, ‘Ghazal: To Hold Me’ and ‘Ghazal [after Hafez]’ – channel intense emotion. Khalvati’s ghazals take on a significantly different tone to the sonnets in the section; they are rushing, emotive, and even desperate. Indeed, the name ‘ghazal’ comes from the agonised cry of the gazelle when it is cornered, and was traditionally used by writers like Hafez and Sa’adi for purposes of lamentation and preoccupation over a beloved. While the unrhymed, lyrical sonnet sequence enables Khalvati to ponder over the garden universe of her childhood, the ghazals enable a rhapsodic tone:

I want to die being held, hearing my name

thrown, thrown like a rope from a very old pier to hold me.I want to catch the last echoes, reel them in

like a curing-song in the creel of my ear to hold me.[5]

‘Ghazal: It’s Heartache’ offers a similar opportunity with its repetition of ‘heartache’. Indeed, specific rules of the ghazal structure unlock intense emotion: for example the repetition of words at the beginning and end of the couplets. Such drumming repetition creates a sense of desperation. Furthermore, the way in which a ghazal consists of autonomous couplets means that one emotion is layered upon by each couplet conveying the same message in different guises to reinforce such fervour. The ghazal’s repetitive and focused form also enables it to showcase the importance of small details for Khalvati. In this way, the poet is able to linger on the image of the Lily of the Valley or the candles of the chestnut trees in two separate ghazals. Her preoccupation with small things reveals how important small fragments and details are in her memory of her childhood. Indeed, her memory is a driving force of the poem.

The ghazal has circulated in English literature for centuries: Tennyson and Hardy wrote ghazals, as did American poets like James Harrison, Adrienne Rich, Robert Merzy, and Galway Kinnell. Like these poets writing in English, Khalvati makes use of the ghazal, most importantly, for its formal possibilities. Undeniably, her interest in the ghazal cannot be separated from her Persian background, but by her showcasing of the possibilities of the ghazal form in English, Mimi Khalvati can be seen as a British poet making use of what is now a widely circulated poetic form in English. Examining the ghazal in Khalvati’s work in this way highlights how the labels placed on non-white or UK-born British writers are so often limiting, leading to the overlooking of direct poetic analysis in favour of an overzealous search for an ethnic and national narrative.

~

Works cited

[1] Vicki Bertram, ‘Mimi Khalvati in Conversation’, PN Review, Vol. 26 No.2, November-December 1999.[2] ed. John O. Hayden, William Wordsworth: Poems, Volume I, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1977, 529.

[3] Marius Koceijowski, God’s zoo: artists, exiles, Londoners, Manchester: Carcanet, 2014, 276.

[4] Khalvati, The Meanest Flower, 21.

[5] Ibid., 27.

Cite this: Fathi, Holly. “The Presence of the Ghazal in The Meanest Flower (2007)” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2018, [scf-post-permalink]. Accessed 28 January 2022.