Close reading of Moniza Alvi’s ‘Eine Kleine Nachtmusik’

William Ghosh

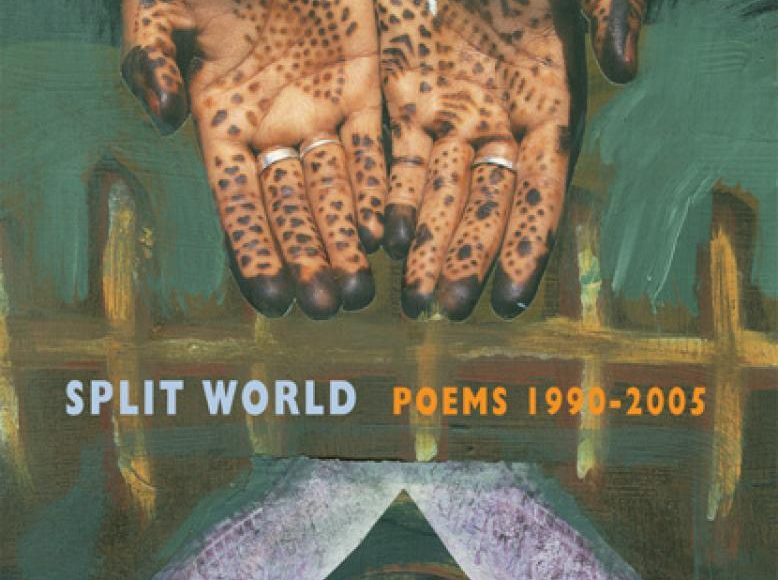

‘Eine Kleine Nachtmusik’ from Split World: Poems 1990–2005 (Bloodaxe, 2008).

Stars glint like metal in their hair.

The darkness, fine as artists’ ink,

Seeps into their nightclothes.

If you follow them down the path –

You turn to stone.

Alvi’s poem, ‘Eine Kleine Nachtmusik’ (‘a little night music’) shares its title with a Mozart serenade (No. 13 for Strings in G Major) and a Stephen Sondheim musical. But its direct point of reference is a 1943 painting, ‘Eine Kleine Nachtmusik’, by the American surrealist Dorothea Tanning. Tanning’s painting shows a young girl on an upstairs landing, passing the figure of a lifeless doll. The hair of the girl flies upwards, as if in a gale, whilst tendrils from a giant sunflower lie on the red carpet in her path.

Alvi’s poem forms part of a sequence of poems about parents and children. Her conceit is that the girl in the painting is in fact a depiction of ‘daughters’ as a species. ‘You can lock the doors,’ she writes, ‘even / bolt the air, but there’s no way / of keeping your daughters in at night’. ‘It doesn’t matter how old they are’, sooner or later ‘a tornado throws them down the path / and ravishes them’.

The principal meaning of ‘ravishment’ seems to be something like rapture: being seized or transported by something beyond anyone’s control. The surreal image – ‘Stars glint like metal in their hair’ – inverts a realistic simile in which metal trinkets in dark hair ‘glint’ like stars. In this way, Alvi suggests a connection between this cosmic, fantastic ‘ravishment’ of the tornado, and the apparently-mundane upheavals and excitements of childhood: Claire’s Accessories, dressing up, plastic gems. If stars are like metal trinkets then metal trinkets are also like stars. In a similar way, the image of the parent ‘turning to stone’ on the garden path could conjure up fantastical images of Medusa, but it also suggests the embarrassment of a parent watching their daughter escaping ‘down the path’ into a social world of her own.

‘Ravish’ also has sexual connotations, of which Alvi is well aware. Though the first verse-paragraph of the poem is about young children, the second – which describes the daughters as ‘flung back into the hallway’ ‘long after the midnight hour’ – alludes to adolescent experience. How long is this night-time tempest, then? What is the time span of the poem? Alvi is describing a single, surreal night, but her referent is the tornado of childhood – specifically, girlhood – itself. For parents, this process is half-concealed – taking place in upstairs bedrooms or at school – and it ends uncomfortably soon. They meet their daughters returning at midnight with ‘their blouses open like curtains / on their narrow, childish chests’.

A reviewer in the London Magazine has spoken of the ‘metaphysical wit’ of Alvi’s poetry. The allusion is to early-modern ‘metaphysical’ poets such as John Donne whose elaborate or unexpected metaphors make unlikely connections visible, and prompt the reader to see the profound spiritual significance of mundane, local events. Alvi’s verse, at its best, does this too, and its ‘wit’ is not just sparkiness. Her fantastic excursions register the fabulous aspects of everyday experience, marrying imaginative wonder with a wry, mature intelligence.

Cite this: Ghosh, William. “Close reading of Moniza Alvi’s ‘Eine Kleine Nachtmusik.’” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2017, [scf-post-permalink]. Accessed 31 January 2022.