George Floyd and Steve Biko: Vital Points of Connection

Daniele Nunziata

Current Black Lives Matter protests are putting unprecedented pressure on the racial injustices which Black people face in all walks of life in this country and elsewhere. People are marching defiantly through major cities across the globe to demand that the legacies of colonialism and systemic racism be dismantled.

The very specific and haunting atrocities which catalysed these demonstrations, such as US segregation, South African apartheid and UK anti-immigration policies, are not isolated occurrences however. Governments are continuing to fail to redress centuries of colonial oppression.

It is vital that both historic and contemporary narratives of Black experiences are read as a stepping-off point in the pursuit of justice. This includes the compelling writings of Steve Biko whose conceptualisation of Black Consciousness, and his own tragic killing at the hands of apartheid authorities, signal urgent points of connection between the past and present which deserve renewed recognition.

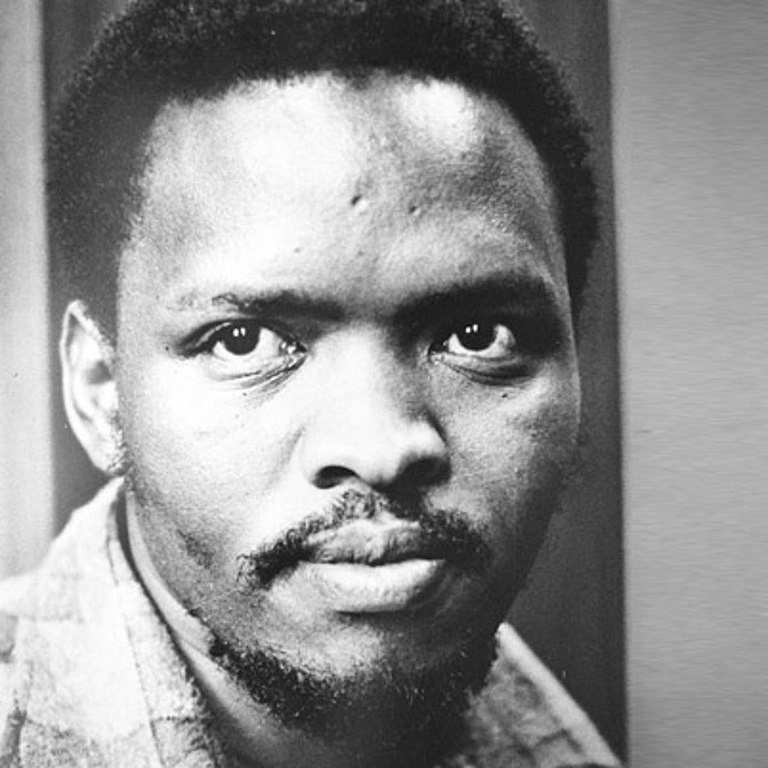

As the world responds in horror, sadness, and anger to the murder of George Floyd on the streets of a city and country he called home, we are compelled to think of other Black lives cut tragically short as a result of racist, institutionalised violence. One such man was Bantu Steve Biko, a Xhosa South African activist who campaigned tirelessly against the apartheid regime. He was beaten to death in 1977 by security officers who had imprisoned him days earlier for entering Cape Town (after he was banned from travelling to the city). He was only 31. Many consider his arrest a set-up; his murderers were never prosecuted for their actions, even after the 1994 Truth and Reconciliation Commission was created.

Biko’s brutal murder had a palpable impact on South Africa and the rest of the world, sounding a forceful wake-up call to non-Black citizens who wilfully overlooked the inhumane cruelty of apartheid. As well as impacting the politics of well-known figures like Nelson Mandela, Biko continues to be a source of inspiration today; his name has been leant to numerous organisations including the Steve Biko Foundation which has developed projects like Accelerate Hub to support young people across Africa.

In his lifetime, Biko’s activism was immense and he spearhead the Black Consciousness Movement, an organised form of resistance directly responding to the 1960 Sharpeville massacre in which 69 Black South Africans were killed in a police station in Transvaal. He also established the Black People’s Convention in the 1970s and his campaigning drew inspiration from Black Power organisations in the US. He often gave keynote speeches at these events and published his words under name ‘Frank Talk’, chosen for its deliberate double meaning.

Many of his writings were posthumously collected in the 1978 anthology I Write What I Like. It is compulsory reading for everyone – especially as a way of understanding his nuanced theories and expositions of racial inequality and racist violence. In the preface to this collection, the editor Aelred Stubbs grappled with Biko’s passing, suggesting that while it was difficult to directly comment ‘in depth about his death’ or to begin writing a biography of him, Biko’s teachings were desperately needed: they were, and sadly continue to be, ‘timely, [as they] serve to inform those who all over the world know the name Biko only in the dreadful context of his death’. There are haunting echoes of what his happening, ‘all over the world’, today.

The title of the collection comes from the opening words of one of the essays, ‘We Blacks’, in which Biko outlines his definition of Black Consciousness. In his personal, first-person address, he asserts that apartheid ‘is obviously evil’ and ‘has been tied up with white supremacy, capitalist exploitation, and deliberate oppression’. These linked forms of subjugation lead to his conclusion that: ‘Material want is bad enough, but coupled with spiritual poverty it kills’. This combination of economic and psychological forces, alongside physical violence, result in the fatal oppression of Black people in South Africa and beyond. (Note that the Civil Rights Act in the US had only been established a few years earlier in 1964.)

As well as addressing the socio-economic inequalities caused by racist political systems, Biko is also passionate about counteracting this second, internal category of ‘spiritual poverty’ which feeds off, and deepens, external monetary poverty. Accordingly, the ‘first step is therefore to make the black man come to himself; to pump back life into his empty shell; to infuse him with pride and dignity […] This is what we mean by an inward-looking process. This is the definition of “Black Consciousness”’.

Part of this process involves revising Eurocentric depictions of the past, ‘to seek to rewrite the history of the black man and to produce in it the heroes who form the core of the African background’. Interestingly, Biko himself has become one of these ‘African heroes’ whose life, teachings, and activism must be urgently recalled today and always. As he states in another essay in the collection, ‘what is necessary as a prelude to anything else that may come is a very strong grass-roots build-up of black consciousness such that’ Black people ‘assert themselves and stake their rightful claim’ in a given society.

Movements like Black Lives Matter offer a version of these ‘grass-roots’ organisations for which Biko advocated. They challenge anti-Black racism – in the US, the UK, and across the world – by unapologetically stressing the worthiness, the importance, and the value of each individual Black life existing within a system which derides all Black experiences as a whole. Black Consciousness remains a vital lens through which these ideas are being conveyed. In fact, Steve Biko was the great-uncle of Cherno Biko, the founder of Black Trans Lives Matter.

It is unjustifiable that the kinds of racist murders which occurred in apartheid South Africa – from the massacre in Sharpeville to Biko’s own killing – are still happening in the twenty-first century. Many are quick to list the apartheid regime as one example of the most oppressive forms of political system in living memory, but very few are willing to address the very tangible links between the sanctioned killings of pre-1994 South Africa and the murders of Black people now in the contemporary moment. These murders are often covered-up and surviving loved ones are denied any legal justice by corrupt conspirators. Black Lives Matter demands these killings be heard so justice can be found.

It is easy to see the killing of Biko as a turning-point in South African history. However, we must also strive so that the demonstrations and activism occurring now, in every continent, against institutionalised racism will offer a comparable turning-point for world history. May we long remember Biko’s words and legacy, and may we campaign to seek justice for the countless Black people of all genders, ethnicities, sexualities, and nationalities who have been murdered because of their race. These include George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and David McAtee this year alone in the US. We must never forget their names.

Cite this: Nunziata, Daniele. “George Floyd and Steve Biko: Vital Points of Connection.” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2020, [scf-post-permalink]. Accessed 28 January 2022.