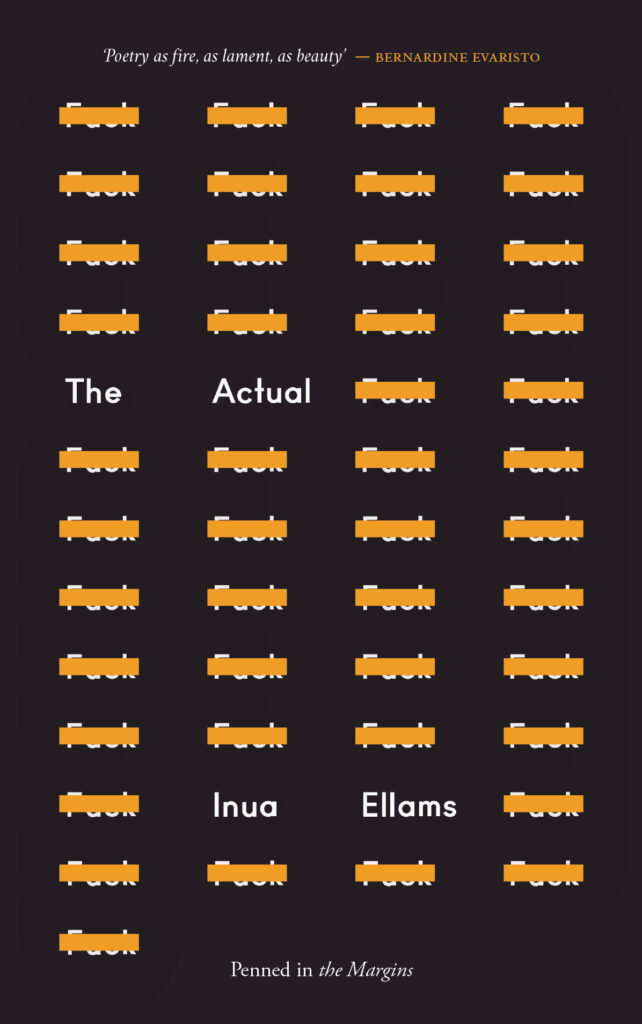

Close reading of Inua Ellams’s ‘Fuck / Tupac’ from The Actual

Chelsea Haith

In this short essay we take a closer look at how Ellams’s verse integrates contemporary cultural references and larger classical and traditional frameworks. As we will see, his poems often function as a way of ‘writing back’, criticising patriarchal or male-dominated structures that are not only harmful to women, but, just as crucially, define men and masculinity in traumatising and violent ways.

In ‘Fuck / Tupac,’ the first poem in the collection The Actual, Ellams identifies connections across race in working-class struggle and gang warfare.

Fuck / Tupac

for dying early / for the fields of lavender and hawthorn in which I sat / overlooking Dublin City / though / as dusk wrapped the sky / it could have been any creaking constellation of traffic and tower blocks / from Compton to Clondalkin / blinking staccato madness / into the unspooling night / Fuck you / for forcing the criminal animal gnashing its teeth in piss-streaked alleys / collarless priests cruising in rented hatchbacks / Protestants and Catholics / like Bloods and Crips / brothers split along colour lines / fuelled by racist police / who came to break our skin

In the first lines, the reader is called to notice Ellams’s experience of dislocation in his adolescence in Dublin, heightened by the distance he feels from the city he sat ‘overlooking’ as well as the place he first emigrated from, that is, Jos in Nigeria. Ellams also highlights the similarities between the gangs of the 1980s and 1990s Los Angeles rap scene (the Bloods and Crips) and the violence of the religious and political ‘Troubles’ that divided Ireland and Northern Ireland in the second half of the twentieth century (Protestants and Catholics). Tupac (also known as 2Pac and Makaveli) was a leading rapper, perhaps one of the most representative artists associated with early American West Coast hip hop (the name Makaveli references the linguistic genius of Italian Renaissance diplomat Machiavelli). Ellams laments the split that he identifies between ‘brothers’ in both contexts. ‘Brothers’ in this case are not defined by racial or fraternal connection, but by class and poverty: that is, young underprivileged men are made ‘brothers’ through their mutual wage-slavery or the bonds of unemployment, but are divided unnecessarily by race and violence.

The speaker in the poem laments Tupac’s tragic assassination at the age of twenty-five in gang warfare in LA. Tupac fell victim to the same attitudes of honour and pride in one’s masculinity and social power that fuelled the gang wars, and which he referenced and called out in his work. At the same time, Ellams points to his own struggle to come to terms with social divisions and the violence that proliferates from them, noting most significantly their universality, ‘from Compton to Clondalkin’. He reminds the reader that the ‘collarless priests’ of the Troubles have much in common with West Coast gangsters and share their desire for power and recognition. The term ‘brothers’ points both to the priests, as well as Christians more generally, and to black men who identify transnationally with one another’s experiences of racial violence. Yet at the same time they respond to these experiences in hypermasculine ways, often with tragic consequences – as in the death of Tupac.

It is significant that Ellams begins his provocatively entitled collection with this angry mourning for the loss to arts, culture and history that follows as a direct result of toxic masculinist violence. The work continues in this vein, highlighting his grief through the emotive ‘fuck’ that begins each poem. Ellams is uncompromising in expressing his views about the impact these social issues have had on his life and lives like his own. He mediates constantly between different cultures and places, drawing on multiple contexts to make himself heard.

Works cited

Armitstead, Claire, and Inua Ellams, “Interview: Inua Ellams: ‘In the UK, black men were thought of as animalistic’”, The Guardian online, published on 22 April 2019, accessed on 2 December 2020 from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/apr/22/inua-ellams-poet-playwright-cultural-impresario

Jarrett-Macauley, Delia, “Inua Ellams – Critical Perspective,” British Council Literature, published in 2018, accessed on 2 December 2020 from https://literature.britishcouncil.org/writer/inua-ellams

Nwaozuzu, Uche-Chinemere, “Inua Ellams’ The 14th Tale and the Concept of the Outsider,” Nsukka Journal of the Humanities, vol. 24, no.2, 2016: pp. 81-87.

Cite this: Haith, Chelsea. “Close reading of Inua Ellams’s ‘Fuck / Tupac’ from The Actual.” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2021, [scf-post-permalink]. Accessed 29 January 2022.