The Myth of Homecoming

Lotta Schneidemesser

This essay first appeared in The Oxonian Review

If a man is to die defending a field, let the field be his field, the land his land, the people his people.

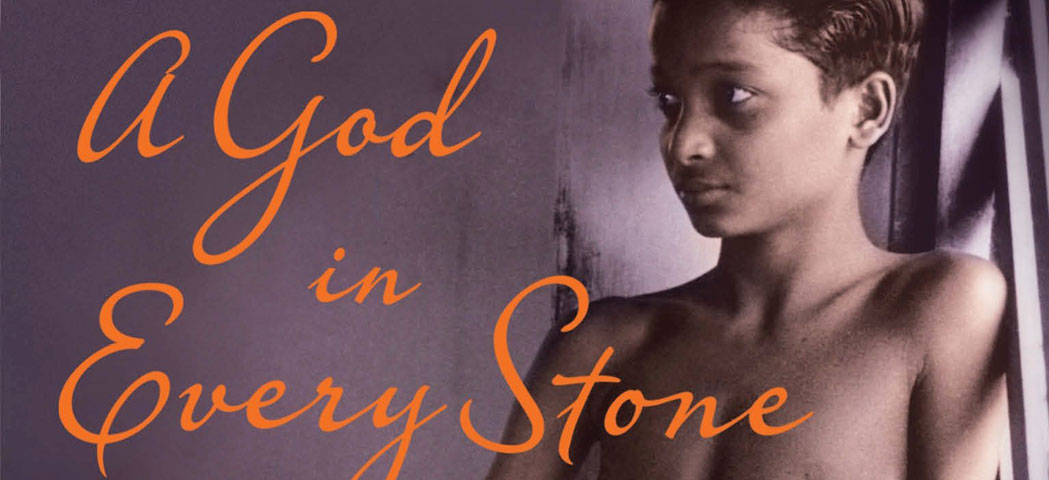

In A God in Every Stone (2014) Pakistani novelist Kamila Shamsie weaves in elegant, captivating prose a story that takes the reader through time and across continents, from the reign of the Persian King Darius in the 5th century to the experience of the battle of Ypres in WWI by Indian soldiers, and ultimately to the fight for Indian independence in Peshawar. The novel tells the stories of the British archaeologist Vivian Rose Spencer, the Pashtun soldier Qayyum Ghul and his younger brother Najeeb, whose intertwined fates culminate in a tumultuous finale in the streets of Peshawar.

Kamila Shamsie has won numerous awards for her books, including the Pakistan Prime Minister’s Award for Literature, and the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. In 2000 she was named one of Orange’s 21 Writers for the 21st Century. Born in Pakistan in 1973, she grew up in Karachi, studied in the US and currently lives in London. Her first four novels are all principally set in Karachi; in an interview with Helen Brown, Shamsie has explained that her decision to set her works there arose from her own homesickness – she wrote her first novel while living in the US – and that for her writing became “a way of recreating the world on the page.”

A God in Every Stone is a historical novel that deliberately interweaves real events with fictional ones; although historical fact structures the fiction, the characters themselves are the ultimate driving force. The figure of Qayyum Gul returns to Peshawar after having fought in World War I and being wounded in the battle of Ypres. Upon his homecoming, he decides to join the non-violent opposition against British colonial rule under Ghaffar Khan, a close associate of Mahatma Gandhi. Qayyum’s homecoming is the turning point of the novel; the scene of action changes from war-ridden Europe to Peshawar, the city of his birth and the place where his family lives. Because he has lost an eye in combat, he is treated in a field hospital before being discharged and sent back. The reader accompanies him on the last part of his train journey, and whilst we are given access to his thoughts—“Almost home now – Allah forgive him, he’d rather be in the trenches” — we are given no explanation as to why he might wish to be back in war-torn Europe.

Qayyum’s homecoming is not, as one might anticipate, a joyful occasion; it is a moment of tension and alienation. The words “home” and “trenches” are diametrically opposed. Whereas the term “home” might usually be associated with familiarity and safety, and “trenches” conversely with the danger of war, for Qayyum, the inverse is true. The trenches have become a familiar space, whereas the home to which he returns after several years of absence now feels utterly foreign. In the trenches, Qayyum has shared a sense of camaraderie with his fellow soldiers, “his people”. However, on returning to Peshawar, he feels little affinity with the merchants, traders, and beggars whom he sees in the streets. He enjoyed the thrill of battle and derived self-worth from being part of the war, feeling pride in wearing the uniform of his regiment (the 40th Pathans) but now returns home as an invalid and feels dislocated and purposeless. Isolated from those around him, Qayyum seriously questions his identity.

When asked what had inspired her to write the novel at a recent discussion as part of the Great Writers Inspire at Home TORCH series, Shamsie said that for her the most powerful movement in Pakistan was the non-violent resistance against British colonial rule during the 1930s. Yet this was a part of history about which she knew very little and which she felt that Pakistan as a nation had simply ignored. The non-violent resistance movement under Ghaffar Khan began as a reform movement. Khan, who was Pashtun himself, initially founded a school in order to educate his fellow Pashtuns and to prevent violent feuds between different tribes. This movement gradually became more political, and inspired by Gandhi’s movement of non-violent opposition against British Rule, Khan founded the Khudai Khidmatgar (“Servants of God”), which more than 100,000 Pashtun joined. Adding that “Pashtuns are often stereotyped as a violent race” Shamsie stated that she had wanted “to tell a story that was unknown, unfamiliar” in order to explore why and how Pashtuns had joined the non-violent resistance struggle. She explained that originally the story revolved around Qayyum’s younger brother, Najeeb, and that only two sentences had initially been dedicated to Qayyum, but that she suddenly realised the novel should be Qayyum’s story, and deleted almost ten months of work. This shift in focus foregrounds the question of Qayyum’s changed loyalty regarding the colonial power.

In the actual scene of homecoming, Qayyum is struck by how small his family home is. On opening the wooden door, his sisters recognise him and, overjoyed, rush to embrace him – but to him they resemble dark shadows. In an instinctive move of self-protection, he steps back and pulls the door shut. Amidst his terror, Qayyum experiences a flashback to the battlefield, and perceives the shadows as enemy combatants – it is only a moment later that it becomes clear to him that these are just his sisters welcoming him. For his sisters and parents, it is impossible to imagine the trauma he has experienced, and it gradually dawns on them that the son and brother whose return they have eagerly been awaiting is no longer the same person. Qayyum’s missing eye symbolises this difference not only in his character, but also in the way in which he views and relates to those around him.

It is difficult for Qayyum to reintegrate into his former life. He is ashamed to have left his comrades and convinced that he could and should have fought harder. However, what initially appears to be survivor’s guilt or shame is a manifestation of the fact that the experience of the Battle of Ypres (which occurred on 22 April 1915 and was the first poison gas attack on the Western front in WWI) has left him severely traumatised. The theme of war trauma permeates the whole novel. As Cathy Caruth points out in her book Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History, at the core of such narratives lies not only the traumatic experience of the war itself, but also the ongoing guilt of having survived it. The onus is on Qayyum to visit the families of his dead comrades who came from Peshawar and the surrounding area. These repeated confrontations with family members further intensify his trauma.

Reviewing A God in Every Stone for the Guardian, Helen Dunmore criticised Shamsie for her fragmentary form of narration, suggesting that her style lacked detail or adequate attention to the characters, particularly regarding the experience of the 40th Pathans in battle. This is rather a sweeping statement: Dunmore’s implied equation of gaps with distance from the protagonist is overly schismatic. It is precisely these gaps in the narrative and the lack of description of actual combat that enrich A God in Every Stone. The battle scenes and the moment of homecoming are portrayed from Qayyum’s perspective, instead of the panoramic viewpoint of an omniscient narrator. He is wounded at the Battle of Ypres, is in extreme pain, and drifts between consciousness and unconsciousness. Even though the reader is not given an objective account of the battle, there are zoomed-in descriptions of particular images visible from where Qayyum lies injured: an ant on a blade of grass, a fellow soldier missing a hand. He concentrates on those things that he can perceive in his narrowed field of vision and with other senses. The missing eye accounts for these narratological gaps, and Shamsie’s fragmentary style leaves room for the reader to fill lacunae with their own imagination.

A God in Every Stone has been compared to Mulk Raj Anand’s Across the Black Waters, written in 1939. Anand’s text can indeed be seen as an early precursor to Shamsie’s novel because it was the first novel written by an Indian author to depict the experience of Indian soldiers in the First World War. It reclaims, as Quleen Kaur Bijral argues, the Indian past of the Great War and narrates the subaltern version of it. Dunmore has asserted that Across the Black Waters immerses the reader to a greater degree in the horrors and bewilderment of the war than A God in Every Stone, arguing that in Shamsie’s novel “the arrival of the 40th Pathans in France and their experiences in the trenches also need more heft”. It is certainly true that in Anand’s novel, the excitement that the protagonist Lalu and the other sepoys feel upon arriving by ship and preparing to travel to the front is explored in more depth. However, Dunmore fails to take account of the main difference between these two novels: whereas Anand’s novel is a depiction of war and of the arrival of Indian soldiers in Europe, the focus of Shamsie’s novel is, as noted, the protagonist’s homecoming and the effect that this has on him and the community to which he returns; the war has altered him, as well as his loyalty to the British colonial power. Questions of trauma and guilt are thus of far greater concern to Shamsie than detailed depictions of war.

Shamsie for her part has emphasised the centrality of loyalty to her novel: loyalty with one’s birthplace and people, or loyalty to the empire. She explained that whilst researching the novel she had come across letters written by Indian soldiers, which showed that most of them had never before experienced the kind of violence they witnessed in World War I, and that the non-violent resistance movement was in many ways a logical reaction. Examining photographs from the time, Shamsie said she had been particularly struck by the similarity between the military uniform and the clothing worn by those who joined Khan’s independence movement. It was, she argued, as though they had exchanged one uniform for another, one army for a non-violent army, in a bid to recapture a sense of camaraderie, community and home.

~

Lotta Schneidemesser is reading for a PhD in English at the University of York. She also translates fiction from English into German.

Cite this: Schneidemesser, Lotta. “The Myth of Homecoming.” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2017, [scf-post-permalink]. Accessed 30 January 2022.