Settlers and Outsiders: British Writers at the End of Empire

Emma Parker, University of Leeds

Emma Parker discusses several white British authors not typically considered as ‘postcolonial’, but whose work nevertheless addresses the long legacies of empire.

For many twentieth century British writers, especially those born in former colonies and dominions, the question of who ‘belongs’ in Britain is a more vexed and complex question than we might at first imagine. Many celebrated figures of the British literary establishment – from Doris Lessing and Penelope Lively to J. G. Ballard – were raised in colonies and settlements of the British Empire. Travelling to Britain in the post-war period, these writers found themselves strangers in an unfamiliar country and culture that they had nevertheless been raised to consider their own. For Ballard, the shock of arriving in post-war London, after his childhood in the Shanghai International Settlement, left him with the permanent sense of reality as ‘a stage set that could be dismantled at any moment’.[1] The collapse of Britain’s Empire ensured that ‘no matter how magnificent anything appeared, it could be swept aside into the debris of the past’.[2]

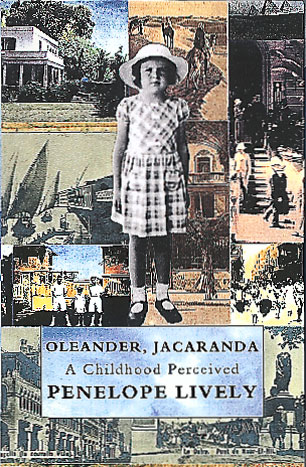

For authors like Ballard, the question of belonging in Britain is by no means straightforward. Similarly, for the Egyptian-born Penelope Lively, who arrived in London in the same year as Ballard, moving from ‘the Middle Eastern world of warmth and colour to the chill grey of England’ was an enormous shock.[3] Lively’s second memoir explains that, although ‘all of us carry through life a kaleidoscopic vision of childhood […] for those who have known “an elsewhere” the quality of these moments are different’.[4] Though often considered a quintessentially ‘English’ writer, this sense of being from ‘elsewhere’ has indelibly marked Lively’s career in Britain. We might associate the role of white, colonial ‘outsiders’ with an earlier generation of writers, including Olive Schreiner, Katherine Mansfield and Jean Rhys, but this cohort of post-World War II authors all raise important questions and anxieties about what it means to be British, or to belong to Britain in the late twentieth century.

Read Penelope Lively’s answers to readers’ questions on Egypt, Englishness and memory.

Born in modern-day Iran (then Persia), Doris Lessing’s early life was spent in Kermanshah, where her father was a bank manager for the Imperial Bank of Persia. After her parents moved to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) Lessing spent her childhood and early adult life in the isolated British colony, before departing for London in 1949. Such was the complexity of Lessing’s relationship with her former homeland that, after writing over six memoirs and autobiographies about her childhood, her last published book stated that she was ‘still trying to get out from under that monstrous legacy, trying to get free’.[5] Although she wrote and rewrote the events of her life many times over, Lessing was unable to escape from the memories of her white settler childhood. In interviews she would claim that ‘everything that’s made me a writer happened to me growing up in Southern Rhodesia, the old Rhodesia’.[6] These early experiences of life on the fringes of the British Empire exerted a powerful influence on her writing career, despite that fact that she lived in London from 1949 to her death in 2013.

Doris Lessing’s response to winning the Nobel Prize for Literature, with archival interviews from BBC Newsnight.

Lessing’s attachment to her memories of empire are complicated by her fierce criticism of white Rhodesian society, which she likened to ‘a mass disease’.[7] All elements of daily life in Rhodesia were subject to a ‘colour bar’, which gave white citizens use of the best public facilities and sole access to skilled jobs and formal education. Yet despite her fierce rejection of the racist, segregated community in which she was raised, Lessing remained deeply attached to the African bush and landscape. In her first memoir, Going Home, she explains that although ‘I have lived in over sixty different houses, flats and rented rooms during the last twenty years […] the fact is I don’t live anywhere. I never have since I left that first house on the kopje [hill]’.[8] For Lessing, living in Britain was not the same as belonging in Britain. In each of her memoirs and autobiographies she suggests the difficulty of belonging to and inhabiting a colonial past which she saw as morally indefensible.

Each of these white writers – Ballard, Lessing, Lively – along with others such as Muriel Spark, J. G. Farrell and William Boyd, shed light on what it means to remember Empire in modern Britain. Elsewhere for Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, Ed Dodson has outlined a need to consider some white British writers within conversations about postcolonial literature, without labelling such authors as themselves postcolonial. These memories of colonial life are especially important because, in twenty-first-century Britain, we often continue to ignore or side-line the impact of empire on our contemporary cultural and political landscape. As Paul Gilroy has argued in a characteristically prescient observation, rather than seriously considering or debating Britain’s colonial past, this ‘unsettling history was diminished, denied, and then, is actively forgotten’.[9] Writers who live and work in Britain, yet retain their unsettling sense of belonging to an ‘elsewhere’, might provide one way for us to look more closely at our colonial histories and to understand their continuing impact upon our present.

~

Notes

[1] J. G. Ballard, Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton (London: Fourth Estate, 2008), p. 58.

[2] Miracles of Life, p. 58.

[3] Penelope Lively, Ammonites and Leaping Fish: A Life in Time (London: Fig Tree, 2013), p. 70

[4] Penelope Lively, A House Unlocked (New York: Grove Press, 2003),p. 107.

[5] Doris Lessing, Alfred and Emily (London: Fourth Estate, 2008), p. viii.

[6] Eve Bertelsen, ‘Interview with Doris Lessing’, in Doris Lessing, ed. Eve Bertelsen, Johannesburg: McGraw-Hill, 1985, 93–120, p. 93.

[7] Doris Lessing, Going Home (London: Panther Books, 1984),p. 17.

[8] Going Home, p. 37.

[9] Paul Gilroy, After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture? (London: Routledge, 2004), p. 98.

Cite this: Parker, Emma. “Settlers and Outsiders: British Writers at the End of Empire.” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2019, [scf-post-permalink]. Accessed 14 July 2024.