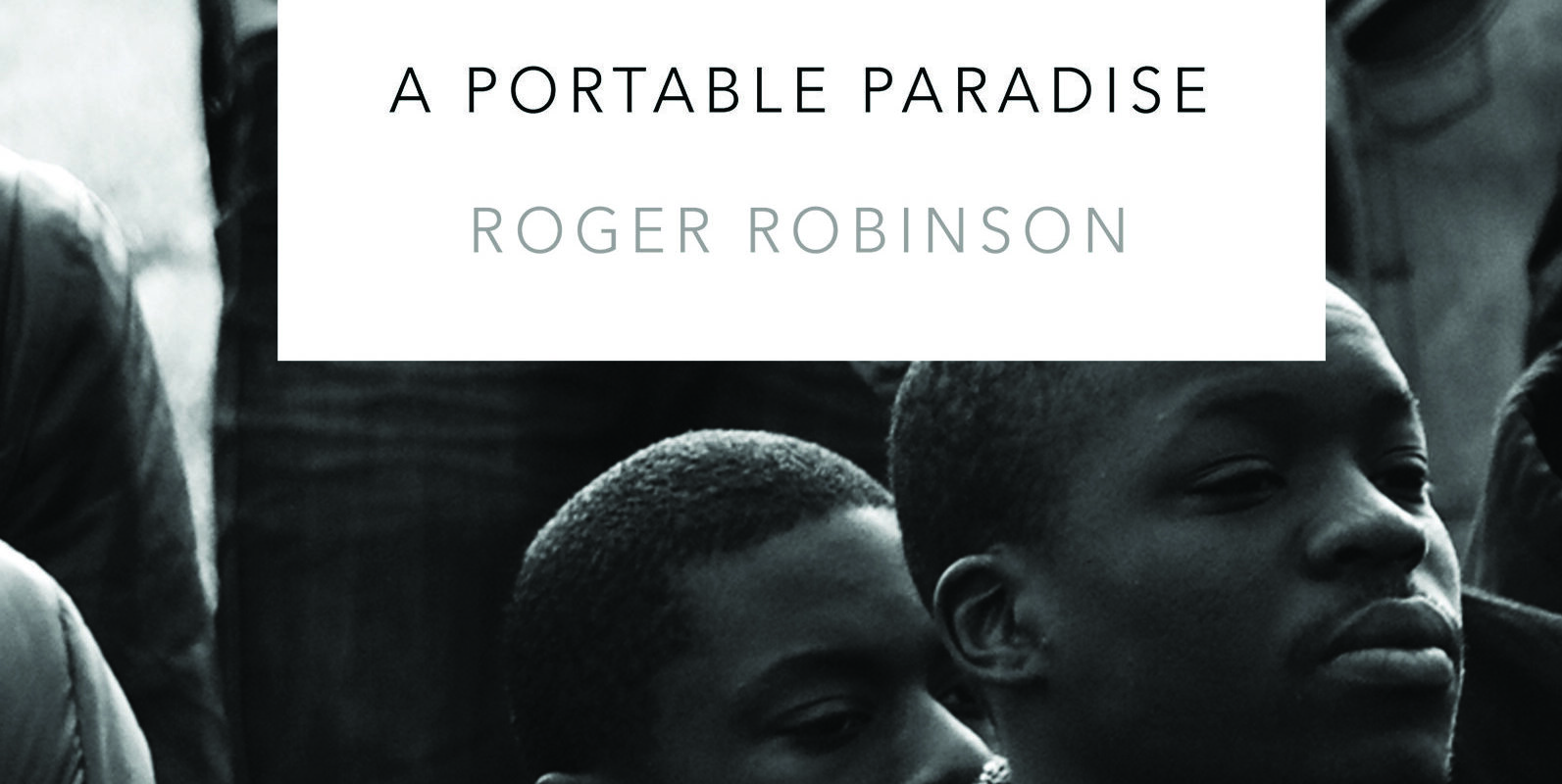

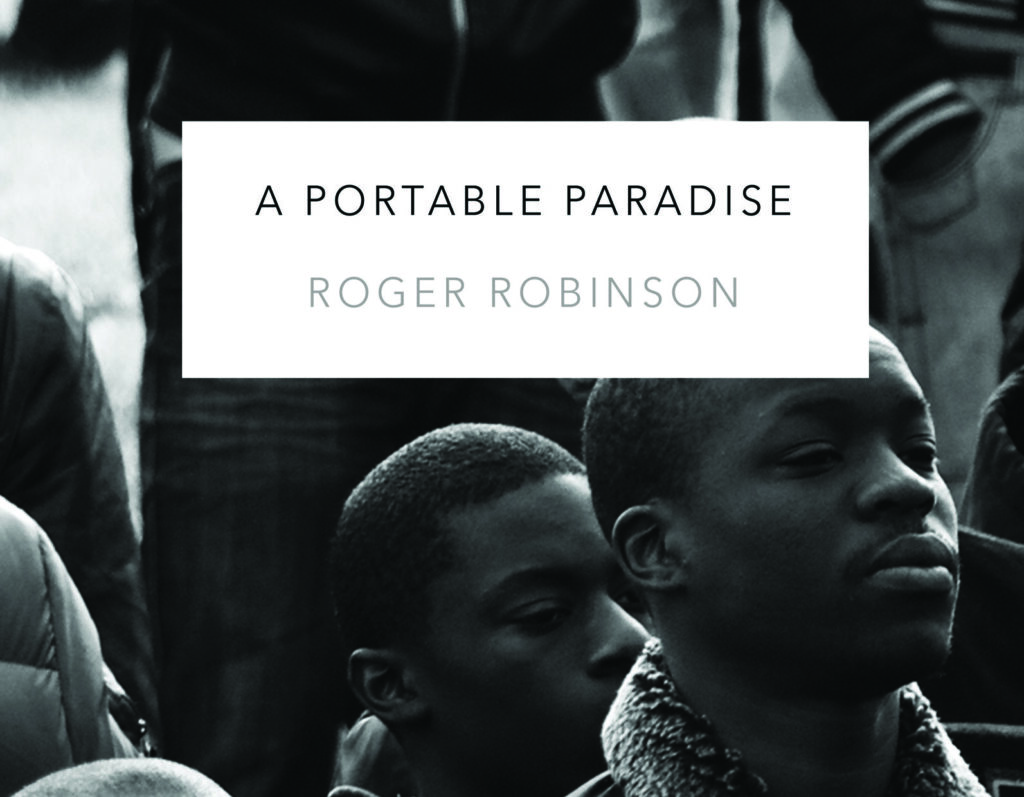

An analysis of Roger Robinson’s A Portable Paradise

Gavin Herbertson

Robinson’s work has always tackled subject-matter and themes which many would consider controversial and has drawn in a diverse array of sources and influences to do so, ranging from Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott to Netflix’s Top Boy. In “Beware”, for instance, the reader is warned about the dangers of police brutality in simple, stark terms:

When police place knees

at your throat, you may not live

to tell of choking.

Written in response to the death of 20-year-old Rashan Charles, who was killed by police in East London in 2017, the haiku feels remarkably prescient in its anticipation of George Floyd’s murder in the USA in 2020. The certainty implied by its opening conjunction, the subordinating “When”, coupled with the purposefulness of the verb “place”, generates the sense that police violence is at once deliberate and inevitable. Robinson’s spoken-word roots are also detectable in the haiku’s orality. The bitter, pained assonance of the long “O” sound in “throat” and “choking”, and the harshness of the plosive alliteration in “police place”, work in tandem to reflect the violence of the act itself.

Elsewhere in A Portable Paradise, and throughout Robinson’s oeuvre more broadly, contemporary concerns are mapped onto older forms in much the same way. In “Slavery Limerick” (2019), for example, Robinson takes the form’s clichéd comic opening, “There once was a man from Nantucket”, but strips it of its humour. His “man from Nantucket” is replaced with Bill, a runaway slave, turned thief, who yells “Fuck it” as he ignores the commands of a man holding him at gunpoint. The humour is subverted by, and supplanted with, the grimness of an execution.

In “Corbeaux” (2019), by contrast, the highly technical villanelle form is employed to explore nature’s inherent cruelty. In a villanelle, two lines are intermittently repeated verbatim across the stanzas before coming together in a terminating rhyming couplet. Inspired by Ted Hughes’s animal poetry – an extract from which is affixed as an epigraph – Robinson’s poem considers the feeding practices of scavenging “corbeaux”, the Francophone Trinidadian name for black vultures. The circling nature of the villanelle form mirrors the motion of the birds, who ‘circle the clouds when something has died’ before descending to feast.

However, it is in the opening section of A Portable Paradise that we find Robinson’s most celebrated verse to date. Therein, readers encounter a series of interconnected poems which reflect on the devastation wrought by the Grenfell Tower disaster (2017; see also Ben Okri’s “Grenfell Tower: A Poem”). The first of these, “The Missing”, presents the fire in terms of religious salvation; its victims are shown ascending to heaven in an “airborne pageantry of faith” (line 36). Through this allegorical conceit, Robinson is able to demonstrate the gulf between the euphemistic manner in which the disaster was discussed by the media and the gruesome reality faced by the victims and their families. In one particularly shocking vignette, from the close of the first stanza, the reader encounters a woman rocking “back and forth” yelling, “What about me Lord, / why not me?” (lines 10–12). Allegorically, she is praying fervently, wondering why she has been left behind on Judgement Day. Non-allegorically, she is traumatised by the fire, screaming for answers, and wishing she had burned to death alongside those she loved.

Robinson’s most recent collection is deeply thought-provoking and utterly necessary. Throughout, he displays a level of technical virtuosity few other poets writing today can match.

Cite this: Herbertson, Gavin. “An analysis of Roger Robinson’s A Portable Paradise.” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2021, https://writersmakeworlds.com/essay-robinson-a-portable-paradise. Accessed 28 January 2022.