A close-reading of Anthony Joseph’s ‘Bosch’s Vision’ from Bird Head Son (2009)

Christopher J. Griffin

The focus of this commentary is on the first poem of Anthony Joseph’s third poetry collection, Bird Head Son (2009). Narrated anti-chronologically, Bird Head Son comprises a series of autobiographical poems that depict the first twenty-three years of Joseph’s life in Trinidad, where he was born. Throughout the collection, Joseph is concerned with the natural world, religion, carnival, and loneliness. These themes are engaged through a mythic, dream-scape conception of the Caribbean.

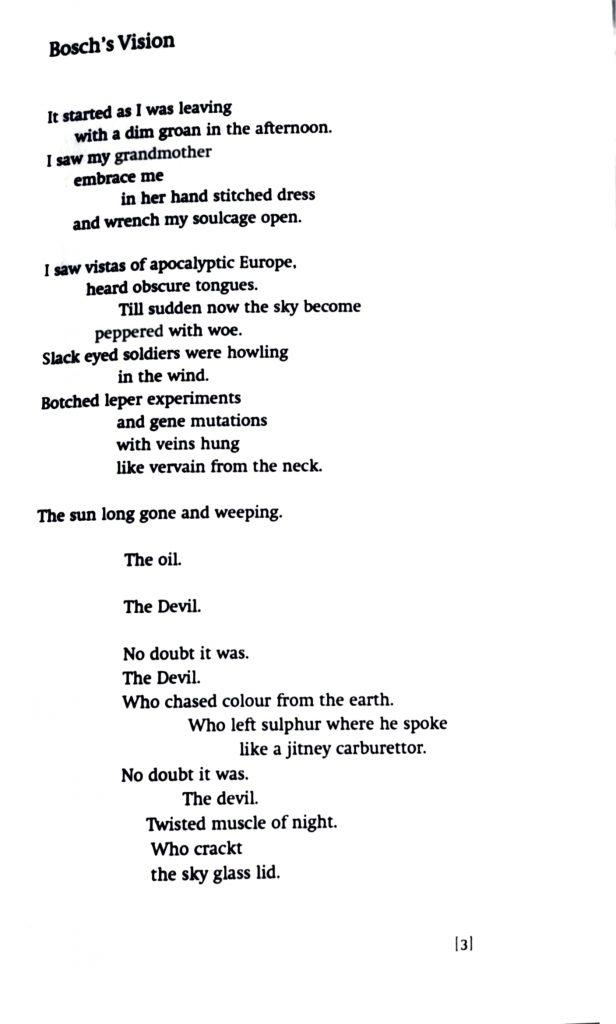

The first poem, ‘Bosch’s Vision’, begins on the day of Joseph’s departure from Trinidad to England in 1989. It narrates an apocalyptic vision of the continent that awaits him on the other side of the Atlantic.

Whilst there are at least five stanzas in the poem, it is unclear how many there are in total. This is due to the poem’s chaotic typography, that is, the layout of the text across the page. The poem is written in free-verse and so lacks a consistent metre, accentuating the sense of chaos. This is further compounded by the poem’s use of enjambment and how these lines are also indented to differing extents, further adding to the impression of an unpredictable vision unfolding through the poem:

with a dim groan in the afternoon.

I saw my grandmother

embrace me

in her hand stitched dress

and wrench my soulcage open. (3)

Subsequently, the speaker experiences prophetic ‘vistas of an apocalyptic Europe’, where they hear ‘obscure tongues’, witness ‘the sky become peppered with woe’, and see a land in which ‘[t]he sun long gone and weeping’. This prophetic quality, both in style and content, reflects the title of the poem, ‘Bosch’s Vision’, a reference to the Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch (c.1450–1516). Bosch is renowned for his often nightmarish and apocalyptic paintings which engage with religious concepts and narratives, as most famously seen in his The Garden of Earthly Delights. In choosing a European artist as the inspiration and title for the poem, Joseph appropriates Bosch’s visions of a biblical Hell and inserts, in its place, a European one, whose maritime climate and various, unknown languages are grave threats.

The poem’s emphatically Caribbean perspective is intensified by the speaker’s vision of the military in Europe: ‘[s]lack eyed soldiers were howling / in the wind’. This echoes the language of one of Joseph’s major influences, Kamau Brathwaite, who described how the poetry of the Caribbean falls outside of European senses of rhythm and metre with reference to hurricanes:

The hurricane that came through into the Caribbean every year began to howl in my ears and as I listened to that sound of another death I knew however that it wasn’t howling in pentameters… That is not pentameter. (Brathwaite 1992: 5)

Whilst Caribbean hurricanes do not howl in pentameter, the soldiers in the winds of Europe do. If not for the syntactic break in ‘[s]lack eyed soldiers were howling / in the wind’, the line would be in iambic pentameter. At the level of metre, therefore, Joseph evokes a conflict between European and Caribbean perspectives. Relatedly, in other works, Joseph has directly connected his need to write experimentally with a desire to avoid being ‘re-colonized’ by Britain (Joseph 1997: 18).

Rapidly, the poem moves into a more biblical but no less personal image: pairing the extraction of ‘oil’ in Trinidad with ‘The Devil’, ‘who chased the colour from the earth. / Who left sulphur where he spoke / like a jitney carburettor’. In Trinidad and Tobago, a jitney is ‘a small pickup truck with an enclosed cab’ (Winer 2009: 469). This mention of a vehicle marks an anxiety that is expressed with greater clarity later, when the speaker travels ‘to the airport’ to leave Trinidad. Indeed, immediately after the parallel is drawn between oil and the Devil, the speaker expresses ‘No doubt’ that it was the devil ‘Who crakt / the sky glass lid’ – that is, who first exposed the sky as limitless and made lands abroad accessible.

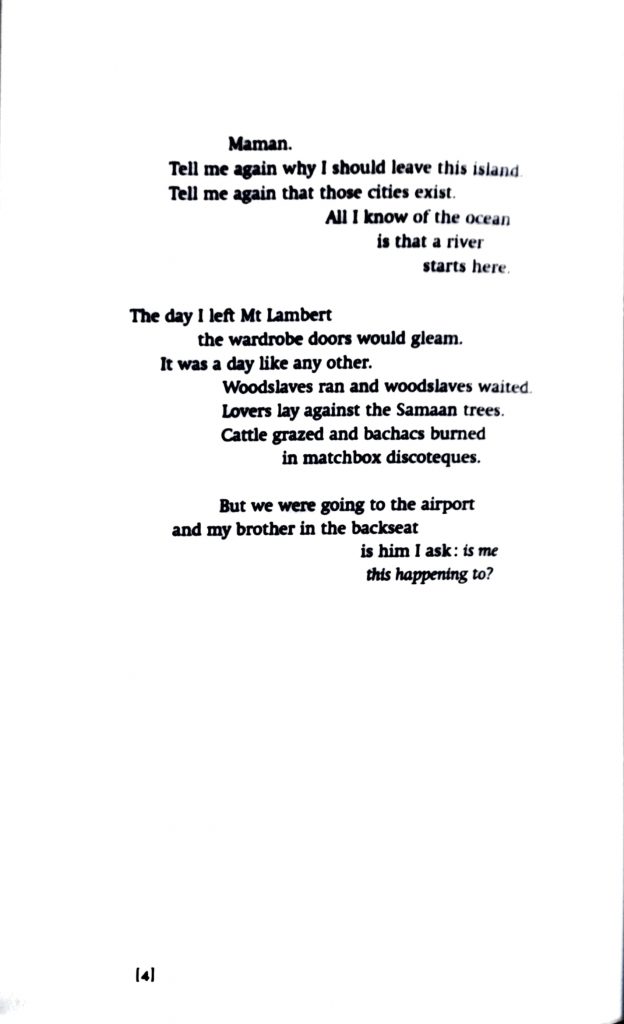

The following stanza highlights one of Joseph’s recurrent interests: the equivocal nature of language. The speaker implores: ‘Maman / Tell me again why I should leave this island / Tell me again that those cities exist’. ‘Maman’, in French, means ‘mother’ (Winer 2009: 561). France frequently occupied the colony of Trinidad and Tobago between 1666 and 1803 and greatly influenced the nation language spoken there. The speaker, then, is expressing a searching vulnerability, turning to their mother to confirm that England is a land of promise. Similarly, however, in line with the biblical undercurrent of the poem, ‘Maman’ can be aurally interpreted as ‘Mammon’ – one of the seven princes of Hell. Mammon represents promises of wealth and material gain, and Joseph has spoken about how writers in the Caribbean are compelled to leave in order to have a career as a writer. More than anything else, England represented access to books and educational opportunities. Here, Mammon is implored to hear the speaker’s anxious pleas and confirm that the European hell their soul has witnessed will bear these opportunities.

This sense of fearful apprehension intensifies near the end of ‘Bosch’s Vision’, at the level of form, as the speaker approaches the airport. The speaker’s relative comfort in Trinidad is implied through the equally indented and self-contained lines:

Woodslaves ran and woodslaves waited.

Lovers lay against the Samaan trees.

Cattle grazed and bachacs burned

in matchbox discoteques. (4)

But the vision begins to trail off and the lines become shorter, before being broken by a new stanza:

But we were going to the airport

and my brother in the backseat

is him I ask: is me

this happening to? (4)

The typography embodies the speaker’s voice: diminutive, askance, and crushed into the corner, expressive of anxiety.

Overall, ‘Bosch’s Vision’ expresses great fear and doubt about the possibilities that the European continent represents, specifically in relation to the climate, the language, and, implicitly, on how England may affect one’s roots in the Caribbean home and one’s ability to write in a manner true to that. All of this is conveyed through a fantastical blend of biblical imagery, multiple languages, and allusions to the impact of Empire on Trinidad and Tobago.

Bibliography

Brathwaite, Kamau, ‘Caliban’s Guarden’, Wasafari 8:16, (1992), 2-6.

Joseph, Anthony, Teragaton (London: poisonenginepress, 1997).

—, Bird Head Son (London: Salt, 2009).

Winer, Lise, Dictionary of the English/Creole of Trinidad & Tobago (Montreal: McGill & Queens University Press, 2009).

Cite this: Griffin, Christopher J. “A close-reading of Anthony Joseph’s ‘Bosch’s Vision’ from Bird Head Son (2009).” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2020, [scf-post-permalink]. Accessed 31 January 2022.