Five years on from Black Lives Matter: The fading echo of curriculum change

Adrian Fernandes

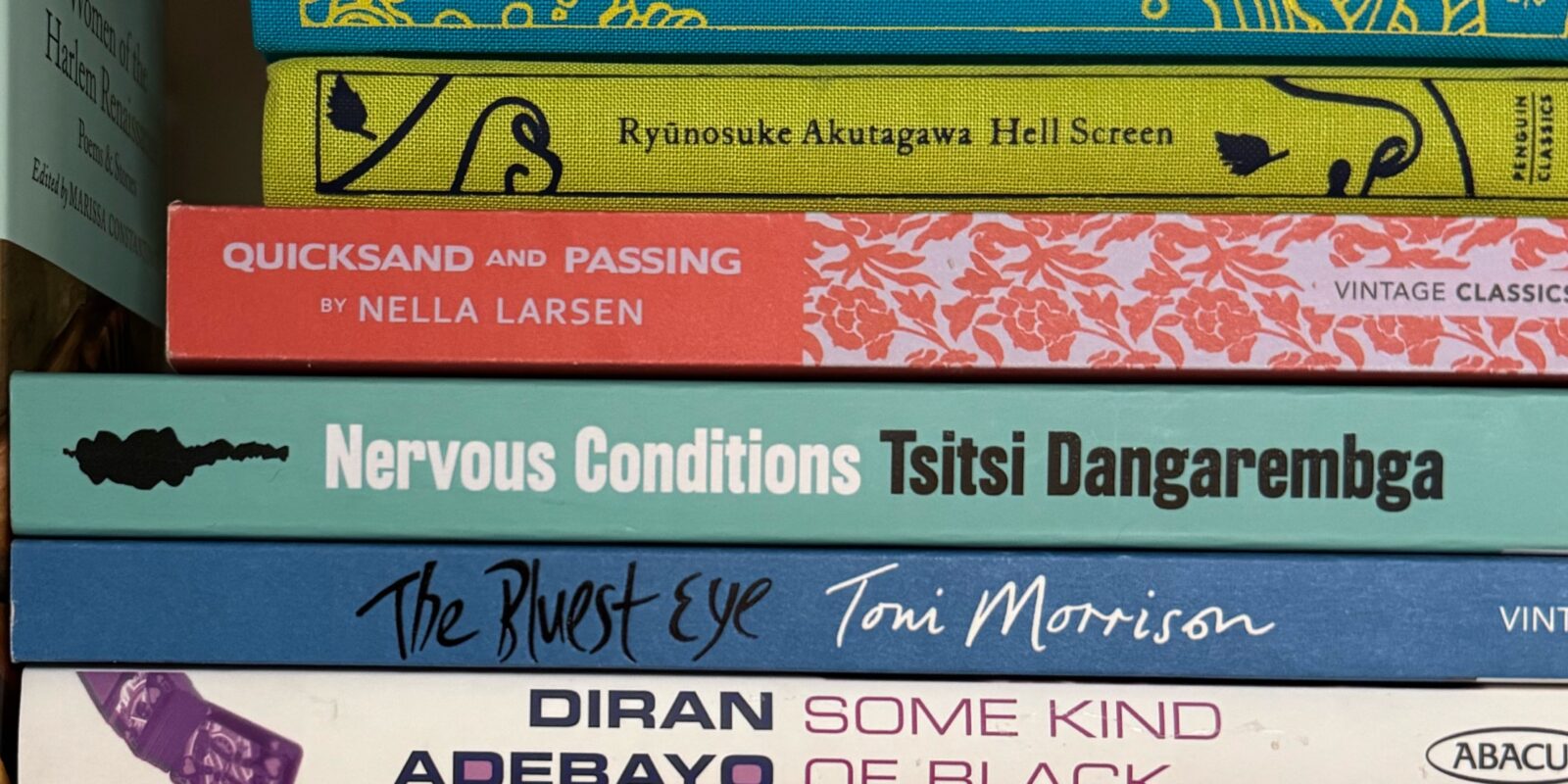

Five years after the Black Lives Matter movement reignited powerful student demands to diversify the English literature curriculum, Writers Make Worlds reviews where we stand now. Our initiative, which rose from diversification interests emerging in the 2010s, reported on the Oxford protests as they happened. The conclusion is clear: the vibrant, student-led energy that pushed for a literature syllabus reflecting students’ lives has collided with institutional rigidity. The promise of 2020 has faded, stifled by deeply embedded barriers.

In 2020, the demand for change was unignorable. Students and young people, with London organisers as young as 18 and 21, orchestrated the largest antiracist uprising in decades. Their emails to headteachers offered detailed critiques, linking the white literary canon to colonial history and systemic racism. For a moment, transformative change seemed an exciting possibility.

Today, that momentum has been absorbed. Recent research with English teachers reveals that, whilst examination boards expanded reading lists, the crucial architecture for implementation was not built. Teachers report a vacuum of training and material resources, forcing a return to (in one participant’s words) a “tried and tested” canon. The white canonical texts by Dickens, Priestley and Stevenson are in the book cupboard, and their familiar schemes of work offer a safe bet in a system that prizes examination grades.

The entire burden of enacting curriculum change was placed upon individual teachers, who simultaneously navigated institutional hostility. Some faced performative allyship – schools that, as one participant said, “chatted a lot but acted little.” Others encountered direct retaliation for their efforts to create change. One teacher, who found a lack of representation after a curriculum audit, was directly threatened by their manager with the words, “If you show this to anyone, I will see you fired.” Where support for addressing change did occur, minoritised teachers were often saddled with unpaid diversity labour, automatically positioned as “the race expert” against their will.

Back in 2020, the profound student engagement with representative texts was neatly reflected in one participant’s joyful remark on reading a minoritised text: “This story feels like my family!” Now, the government’s recent curriculum review offers a new chance to make that feeling of belonging systemic. For this moment to yield a different result, the response must be defined by what was absent before: the concrete investment, dedicated training and institutional courage required to enact lasting change. Without a commitment to implement these core supports, the review – and the diverse, representative curriculum it could enable – risks becoming just another fading echo.

Further reading

Elliott, V., Nelson-Addy, L., Chantiluke, R., & Courtney, M. (2021). Lit in Colour: Diversity in literature in English schools. Lit in Colour. https://litincolour.penguin.co.uk/

Elliott, V., Watkis, D., Hart, B., & Davison, K. (2024). The effect of studying a text by an author of colour: The Lit in Colour Pioneers Pilot. Lit in Colour. https://wp.penguin.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Lit-in-Colour-Pioneers-Pilot-Report-Full-Final-V12.pdf

Peters, M. A. (2015). Why is My Curriculum White? Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(7), 641–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2015.1037227

Shukla, N. (2017, October 25). Adichie, Kureishi, Hurston: what authors should be in the ‘decolonised’ canon? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/shortcuts/2017/oct/25/adichie-kureishihurston-what-authors-should-be-in-the-decolonised-canon

Cite this: Fernandes, Adrian. “Five years on from Black Lives Matter: The fading echo of curriculum change.” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2025, https://writersmakeworlds.com/five-years-on-from-black-lives-matter-the-fading-echo-of-curriculum-change. Accessed 4 December 2025.