The Responsibilities of the Author and the Archive: On the Award of the Bodley Medal to Sir Kazuo Ishiguro

Chelsea Haith

Chelsea Haith, a DPhil candidate at the University of Oxford, was delighted to attend the awarding of the Bodley Medal to Sir Kazuo Ishiguro, and to hear the author in conversation with the Bodley Libraries Head Librarian Richard Ovenden during the 2019 FT Weekend Oxford Literary Festival on 3 April. Here she records and responds to some of the themes raised during this event.

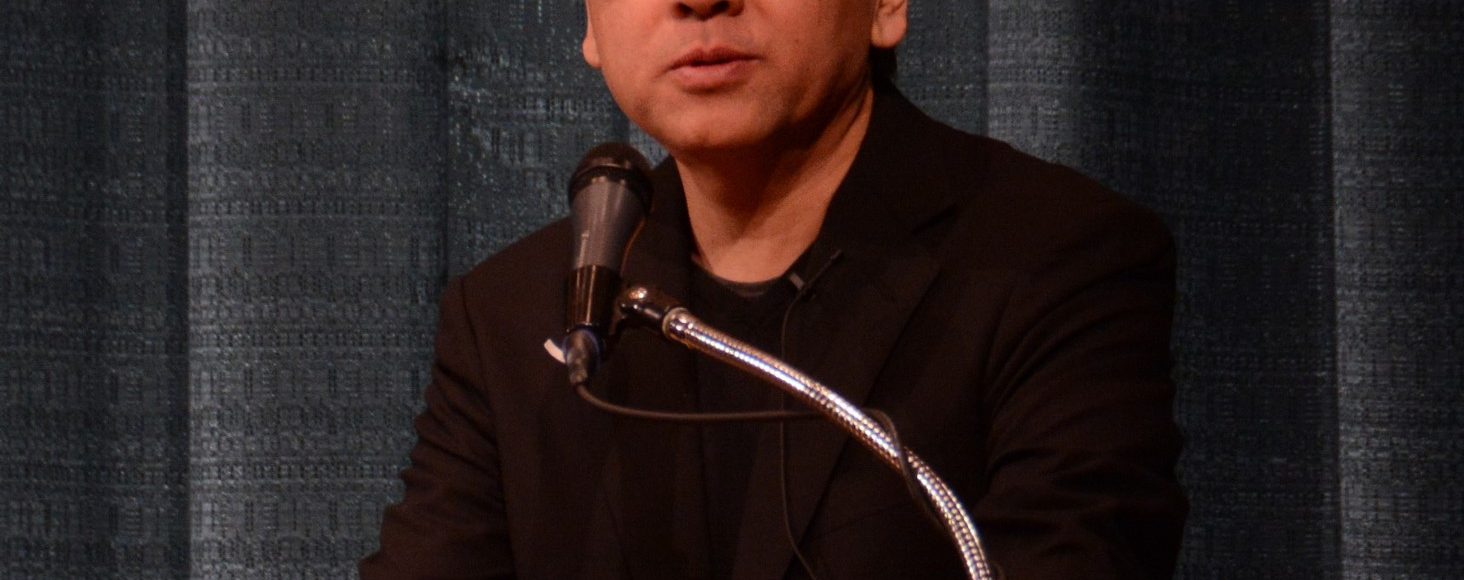

Sir Kazuo Ishiguro knows how to command a room, even when that room is Oxford’s imposing Sheldonian Theatre brimming with an audience in attendance to celebrate his life and work. At the outset he politely interrupts his interviewer, the Bodley Libraries Head Librarian Richard Ovenden, and turns to engage the audience, his wry humour received with appreciative laughter. The audience straightaway relaxed into his confidence. In this moment it’s clear why, had things been different in the early 1970s, his aspirations to make a profession of music, performance and, hence, audience engagement, instead of writing, might well have materialised as he had planned.

Ishiguro is seemingly not intimated or impressed by pomp and ceremony, either, and not given to ceding to expectations. Calm, self-possessed, with the politeness that has become something of a trademark, he proceeded to direct the course of the conversation and indeed the evening. He wore a black suit and white shirt, the top button undone, as in many of his author photographs. Somehow it seems right that the author of The Remains of the Day should eschew convention without utterly upsetting the apple cart. Tie foregone, convention acknowledged and dispensed with, Ishiguro is free to be selectively irreverent, self-deprecating, and to pose difficult questions himself that reflect on the interplay between the past and future, and the role of the author in mediating and responding to the anxieties of our age. He explores the porous, destabilising nature of time in those parts of his work which depict circumstantial loss, and also the subject’s location in time as constitutive of their experience, as well as the unreliable nature of memory.

Prior to the ceremony, Ishiguro had spent the day with Ovenden, learning about the Bodley archives. Now, in front of a packed audience, he wants to know who gets to choose what we remember. For Ishiguro, archiving seems a deeply political project, one that is biased, and which must involve self-reflection at every turn. Ovenden agrees, noting the struggle that archivists have in curating not only the past, but also the present. They discuss the example of the difficulty that archivists face deciding which placards from the 2016 EU Referendum Leave and Remain campaigns should be collected for the records. “As many as possible, from both sides,” is the consensus, though as we know from media representation, certain messages that seem more evocative today are inevitably privileged over others.

On the topic of ethical archiving Ishiguro is relentless, questioning the role and purpose of these physical memory banks, noting access difficulties as well as the problems of potentially useful content becoming lost or overlooked in the sheer volume of material. “Libraries play a crucial role in shaping our memory of who we are, and the narratives that determine who we’ll become. In this sense, writers and libraries share a common – and solemn – responsibility,” he says.

Ovenden calls us back to the archival role of the Bodleian as a reference library, which receives a copy of every item published in Britain, and some texts published elsewhere as well. Newspapers, novels, pamphlets: everything ends up in the Bodleian. However, when the library first came into existence and the Copyright Law was instituted, Thomas Bodley, the library’s founder, did not value or assign much artistic or instructive merit to the novel form. As a result, for example, some first editions of Jane Austen’s works had to be bought later, at great expense. This early folly of the library’s otherwise diligent and forward-thinking founder serves as a reminder that we do not yet know what we may one day value.

Value is indeterminable, just as the future is. Ishiguro wonders whether, for example, his generation of authors have insufficiently addressed contemporary concerns of climate change. He’s equally concerned about the looming threat of AI, but has embraced the possibility of his job becoming obsolete. At home in London, he frequently meets for coffee with a developer from DeepMind. Together, they consider the possibility of AI authors. “Tolstoy III,” is closer than we think, Ishiguro contends. The audience laugh, though some are bemused by the author’s description of his future competitor.

For now, though, authors still have to do the work themselves. The next book is nearly ready, but things such as the Bodley Prize award ceremony keep getting in the way, he jokes. He’s also been writing plays, and collaborated on a successful album with American jazz musician Stacey Kent, for which he wrote the lyrics. However, he writes primarily for the “six or so people” closest to him. His ideal reader is a friend, and while he seems to have come to terms with his success and fame, he’s more interested in talking about ideas than about himself. The larger narratives of nationhood and how groups of people come to conceptualise themselves as such are at the heart of Ishiguro’s interest in collective memory.

Throughout, Ishiguro thinks carefully about the memorialisation of past conquest, and the role of archiving in recording the verity of events. Here is an author responding critically to temporal and technological uncertainty, but always with enthusiasm for the possibilities for creative and humanitarian intervention.

Cite this: Haith, Chelsea. “The Responsibilities of the Author and the Archive: On the Award of the Bodley Medal to Sir Kazuo Ishiguro” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2019, [scf-post-permalink]. Accessed 16 April 2024.