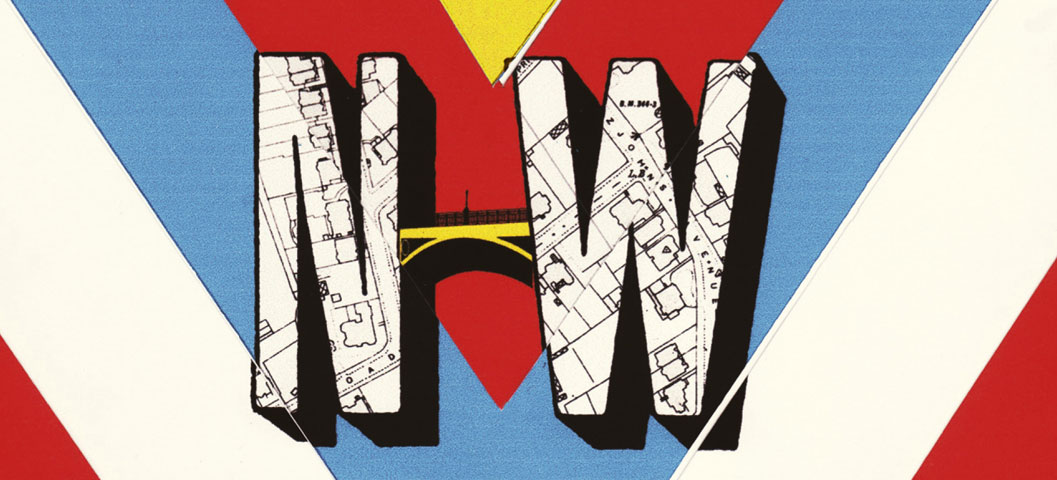

Close reading of NW

Khadeeja Khalid

The analysis is of the following passage from Zadie Smith’s NW (Penguin, 2012), pp. 80–81.

On the way back from the chain supermarket where they shop, though it closed down the local grocer and pays slave wages, with new bags though they should take old bags, leaving with broccoli from Kenya and tomatoes from Chile and unfair coffee and sugary crap and the wrong newspaper.

They are not good people. They do not even have the integrity to be the sort of people who don’t worry about being good people. They worry all the time. They are stuck in the middle again. They buy always Pinot Grigio or Chardonnay because these are the only words they know that relate to wine. They are attending a dinner party and for this you need to bring a bottle of wine. This much they have learnt. They do not purchase ethical things because they can’t afford them, Michel claims, and Leah says, no, it’s because you can’t be bothered. Privately she thinks: you want to be rich like them but you can’t be bothered with their morals, whereas I am more interested in their morals than their money, and this thought, this opposition, makes her feel good. Marriage as the art of invidious comparison. And shit that’s him in the phone box and if she had thought about it for more than a split second she would never have said:

– Shit that’s him in the phone box.

– That’s him?

– Yes, but – no, I don’t know. No. I thought. Doesn’t matter. Forget it.

– Leah, you just said it was him. Is it or isn’t it?Very quickly Michel is out of earshot and over there, squaring up for another invidious comparison: his compact, well-proportion dancer’s frame against a tall muscled threat, who turns, and turns out not to be Nathan, who is surely the other boy she saw with Shar, though maybe not. The cap, the hooded top, the low jeans, it’s a uniform – they look the same. From where Leah stands anyway it is still all dumb show, hand gestures and primal frowns, and of course some awful potential news story that explains everything except the misery and the particulars: one youth knifed another youth, on Kilburn High Road. They had names and ages and it’s terribly sad, an indictment of something or another and also not good for house prices. Leah cannot breathe for fear. She is running to catch up, Olive clattering along beside her, and while she runs she finds herself noticing something that should not matter: she looks older than both of them. The boy is a boy and Michel is a man but they look the same age.

Zadie Smith’s use of narrative voice in this extract from NW allows the reader to delve deeper into the mind of Leah. In this reading, I explore the effects of Smith’s use of free indirect speech as a narrative device, as well as the disparity between Leah’s perceptions and reality.

Smith’s NW is split into several sections, each focalized through a different character. Throughout the novel, Smith uses different narrative forms and techniques in order to fit a specific character or create a certain tone. In this excerpt, drawn from the first section of the novel, Smith employs free indirect speech to knit together the mental machinations of Leah. This form of narration, which combines third-person and stream-of-consciousness narrative, amplifies the sense of an unreliable – or perhaps unlikeable – narrator. Leah and Michel are described as deliberately shopping at a ‘chain supermarket […] though it closed down the local grocer and pays slave wages, with new bags though they should take old bags’ (p. 80). The fragmented narrative follows the pattern of a normal third-person narrative, however Leah’s continual digressions indicate her indecision and establish her as a character with contradictory moral imperatives. This is foregrounded by the unflinching assertion: ‘They are not good people’ (p. 80). This statement may be read as either a self-deprecating observation or a subjective deduction, or both, as the reader cannot confidently ascertain the speaker’s voice.

This sense of uncertainty and fluidity of structure can also be seen in Smith’s rendering of dialogue. Eschewing conventions such as quotation marks to indicate direct speech, Smith creates a reading experience that echoes Leah’s turbulent thought-life. Consequently, the reader must become more accustomed to recognizing individual voices. Smith’s use of dashes further creates a sense of immediacy in the text, as the dialogue is propelled towards a physical clash of confusion, incited itself by confusion, as Leah misidentifies a boy on the street.

Smith’s use of free indirect speech allows the reader to witness and understand Leah’s conflicted mental state. Her distraction and confusion, which gathers a dizzying narrative momentum in the text, ultimately causes a physical altercation that has fatal consequences.

Cite this: Khalid, Khadeeja. “Close reading of NW.” Postcolonial Writers Make Worlds, 2017, [scf-post-permalink]. Accessed 24 April 2024.